(A version of this article was shared with Laughing Place on November 18, 2022.)

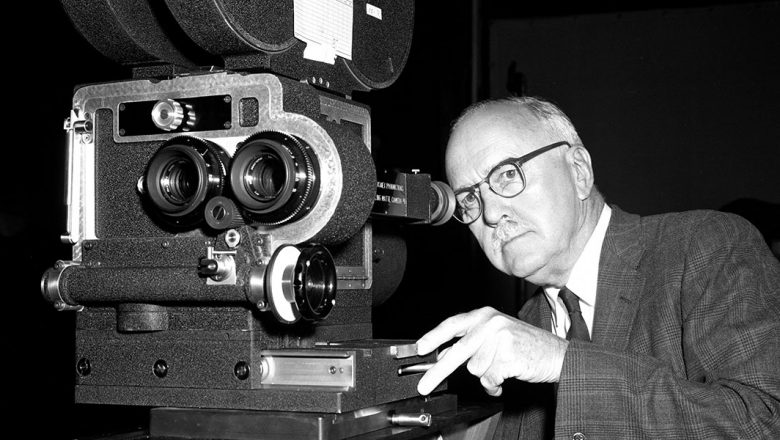

You’ve heard the tale of how Mickey Mouse was born on a train. And we all know Walt Disney was a pioneer of animation from its early days. But do you know the story of the man behind some of Walt’s greatest achievements? Disney Legend Ub Iwerks spent most of his career quietly helping Walt’s dreams become reality.

Let’s dive into the life and accomplishments of this lesser known – but hugely deserving – animation and technical wizard in this edition of Disney Legends Spotlight.

A Working Boy

Ubbe Ert Iwwerks was born in March 1901 in Kansas City, Missouri. Ubbe’s father was a German immigrant who moved to the United States at age 14. His father worked as a barber, and had fathered and abandoned several previous children and wives prior to Ubbe. When Ubbe was a teenager, his father abandoned him as well. As a result, Ubbe dropped out of Northeast High School in 1916 to help support his mother, working full time at the Union Bank Note Company. Sadly, Ubbe was so scarred by his father’s neglect, that he never spoke of him as an adult.

The Birth of Disney Animation

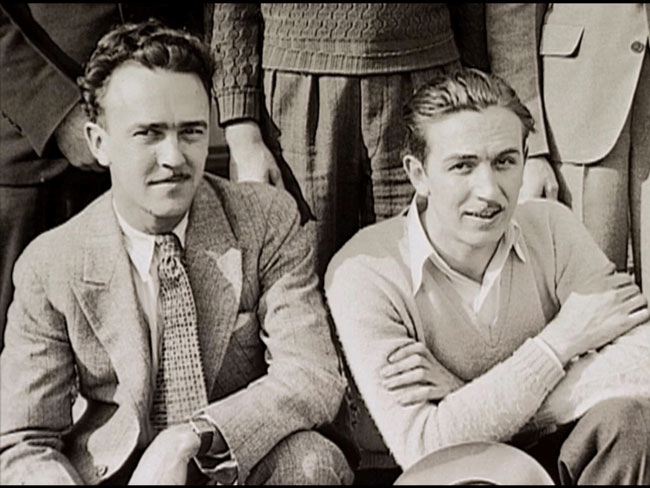

In 1919, when he was 18, Ubbe got a job at the Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Studio, where he was hired to do lettering and air brush work. It was here that Ubbe’s life trajectory would forever be changed, when he met Walt Disney. Walt’s outgoing entrepreneurial manner contrasted Ubbe’s shy, quiet nature, yet the pair immediately clicked.

Both were 19 years old when – after being laid off from Pesmen-Rubin – they decided to start their own business. For a name, they decided on Iwerks-Disney Studio Commercial Artists (they determined that “Disney-Iwerks” sounded too much like the name of an eyeglass manufacturer). In an effort to help keep their fledgling business afloat, Walt took a job as an artist at the Kansas City Slide Company (later called the Kansas City Film Ad Company). Ubbe held down the fort at their studio. However, Ubbe’s quiet, introverted nature was exactly the opposite of the salesmanship that was needed to grow a new enterprise. The Iwerks-Disney studio closed shortly after, and Walt got Ubbe a job working with him at the Film Ad Company.

But Walt wanted to try again. In 1922 he left the Film Ad Company to form his own enterprise called Laugh-O-Gram. Ubbe (who around this time shortened his name from “Ubbe Iwwerks” to “Ub Iwerks”) joined him immediately and was the key animator in producing six modernized animated cartoons based on classic fairy tales. Walt was unable to secure a successful distribution deal for their cartoons, and the business went bankrupt.

On to California

At this point, Walt decided Kansas City was not the best place for him to explore his ambitions. He chose to seek success in Hollywood – the hub of America’s entertainment business. Ub returned to his job at the Film Ad Company. But one little nugget of the pair’s Laugh-O-Gram shorts – Alice’s Wonderland – caught the eye of Margaret Winkler – a film distributor in New York. This short featured a combination of animation and live-action film. Winkler offered Walt a contract to continue making more Alice films. This opportunity resulted in Walt founding the Disney Brothers Studio with his brother Roy in 1923.

Walt himself performed much of the animation for the first few Alice films, but he knew his skills as an animator were limited. So what was Walt’s next step? Contact Ub Iwerks, of course. Walt used his signature charm to convince Ub to move out to California to join the new studio. From the beginning, Ub earned more than anyone else in the studio, including Walt himself. His responsibilities ranged from key animator, to teacher/mentor for the younger animators, to principal artist for marketing posters. The Disney Brothers Studios produced nearly fifty of the Alice Comedies, as they came to be known.

Oswald’s Disappearing Trick

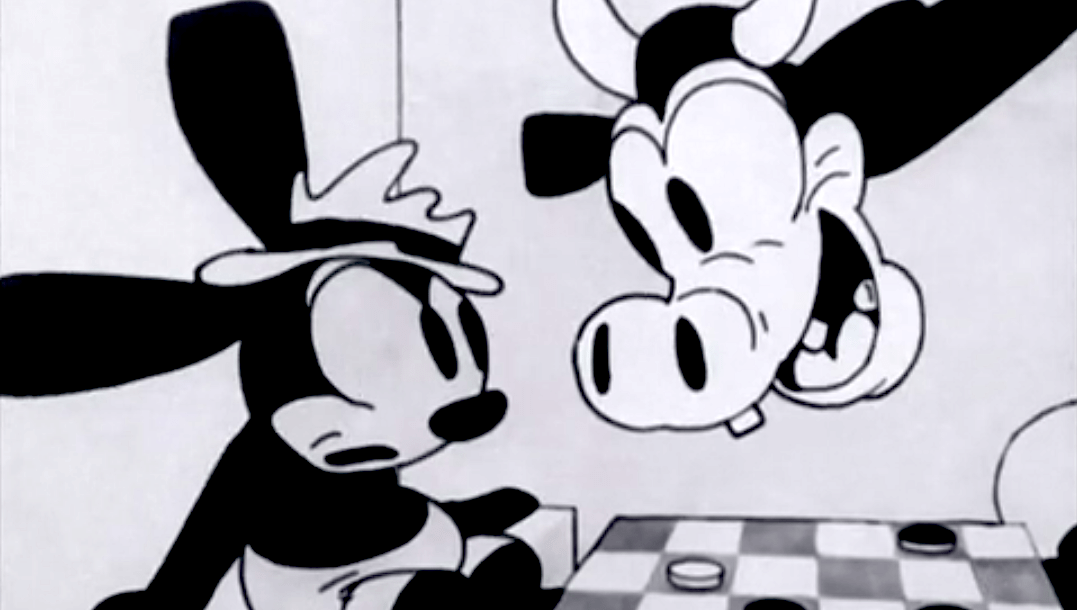

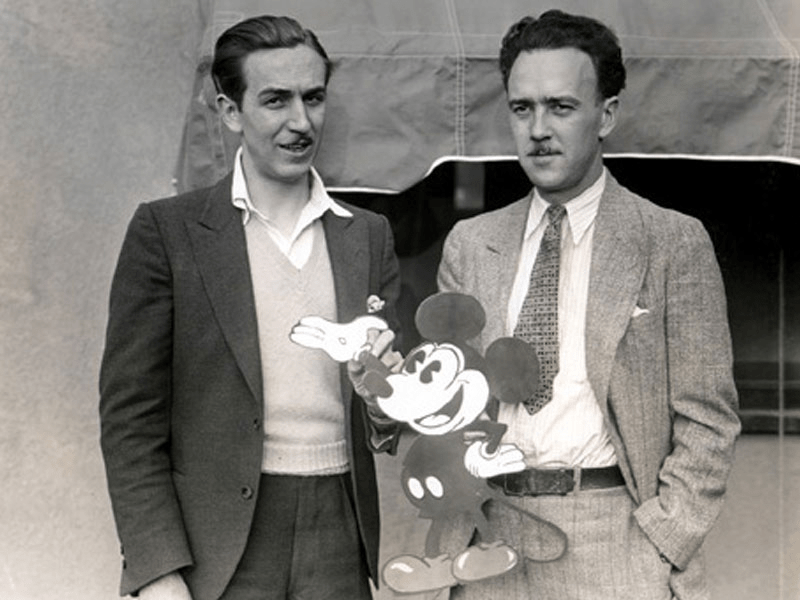

As the studio was nearing the end of their Alice Comedies, Charles Mintz – head of Winkler Productions – asked Walt to develop a new character for Universal Studios. Ub helped Walt create Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. Ub animated almost all of Poor Papa – the first short cartoon in the series. Universal was unimpressed by the first Oswald cartoon, Walt and Ub refreshed Oswald to appear younger and neater, and reintroduced him in 1927’s Trolley Troubles.

Winkler Productions owned the rights to Oswald, and in a shocking and sad series of events, Mintz secretly communicated with all of Walt’s studio artists behind Walt’s back. Mintz asked them to join him in working on the Oswald shorts directly through him at the recently founded Winkler Studio. Mintz was successful in hiring most of Walt’s animators. The only artists who remained loyal to Walt were Ub Iwerks and apprentice artists (and co-Disney Legends) Les Clark and Wilfred Jackson. The Oswald episode hurt Walt deeply, and he vowed to never again work on a character that he did not own.

A Mouse Is Born

But from these ashes arose a new beginning. As legend has it, on the train ride back to California from an unsuccessful last-ditch meeting with Mintz, Walt came up with a brand new character. Walt wanted someone who would personify positivity and cheer, yet also exhibit just enough mischief to be funny without being too much of a troublemaker. The idea of Mickey Mouse was born.

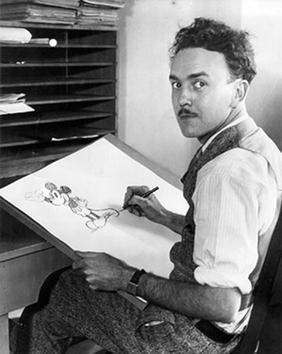

During the final days of Disney’s production of their remaining Oswald shorts, Ub worked very closely (and secretly) with Walt to capture the spirit of his new character. The first three Mickey Mouse cartoons were almost single-handedly drawn by Ub. The lightning-fast animator could produce up to 700 usable drawings a day that were usable (compared to modern-day animators who generally create up to 100 drawings a week).

Trivia Tidbit: Mickey wasn’t Walt’s first choice for the soon-to-be world-famous mouse. He was originally named Mortimer, until Walt’s wife Lillian suggested Mickey would be a much more appealing name.

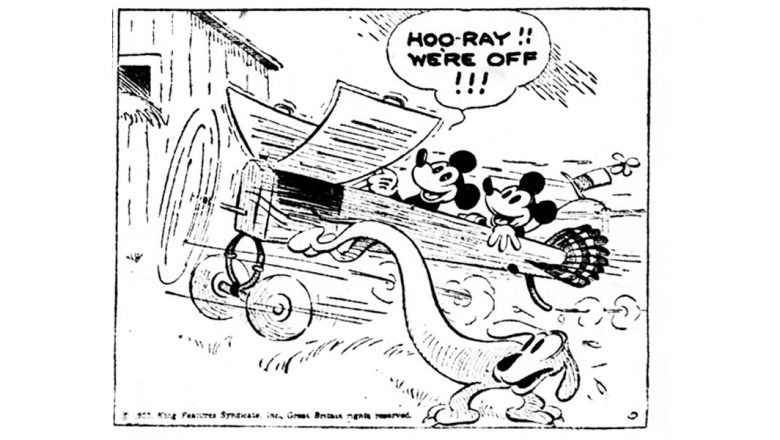

During production of the first few Mickey shorts, Walt pounded the pavement with his mouse, looking for a distributor. Ultimately, it took three tries to get a distributor for Mickey. The first two shorts – Plane Crazy and The Gallopin’ Gaucho – failed to impress test audiences. After a bit of tinkering and character redesign (and the addition of synchronized sound), Walt and Ub found the formula that made Mickey a star. Steamboat Willie – released on November 18, 1928, dazzled audiences, and as such is considered by the Walt Disney Company to be Mickey’s debut.

In Mickey’s earlier days, Ub remained the principal animator. He also took on a mentor role, training young animators on the characteristics of Mickey. Ub also illustrated the daily Mickey Mouse comic strip.

Not wanting to simply rest on Mickey’s success, Walt continued to tinker with the concept of including sound in the animated medium. At the suggestion of the Disney studio’s musical director, Carl Stalling, Walt pioneered a series of unrelated cartoons called the Silly Symphonies. Walt used the Silly Symphonies to experiment further with synchronized sound, as well as other animation concepts. Ub was once again at the forefront of Walt’s next big idea, and he almost single-handedly animated the first short in the series – 1929’s The Skeleton Dance. Shortly after the success of The Skeleton Dance, Walt promoted Ub to a director on the Silly Symphonies series.

Out On His Own

While Ub received plenty of internal credit for his contributions to Mickey’s success, the outward appearance of the Disney Studios didn’t seem to offer the same amount of recognition. Walt’s demands on Ub and the other artists were ever-increasing, and Walt’s personality was getting bigger as well. Ub reached a point where he wanted out from under Walt’s shadow, to find success on his own.

In January 1930, Ub informed Roy Disney of his intention to leave. He had been offered a contract by former Disney distributor Pat Powers to work on a series of cartoons. This contract gave Ub a chance to have his own animation studio and earn twice what he was earning with Disney. Walt took Ub’s departure personally and saw it as a betrayal, and as such he did not try to stop Ub from leaving.

Ub opened the Iwerks Studio in 1930, backed financially by Pat Powers. Under the banner of Celebrity Pictures, Iwerks produced three cartoon series for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) during the 1930s.

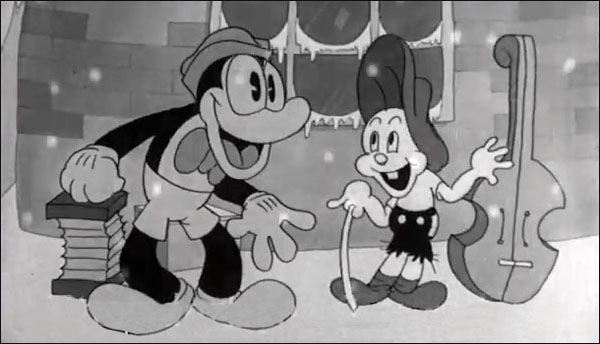

Flip the Frog

Ub’s first project out of the gate was Flip – an anthropomorphic frog, similar to his contemporaries Mickey Mouse, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, and Felix the Cat. Originally conceived by MGM as Tony the Frog, Ub immediately changed the name to sound more appealing. Flip had several recurring side characters in his world as well. Over the course of the series’ three-year run, Flip’s personality developed into a down-on-his-luck character reminiscent of a silent film star Charlie Chaplin.

Flip was consistently challenged with everyday conflicts typical of the Great Depression. Over time, the Flip shorts became increasingly risqué, circling around some concepts and situations that today’s audience would find quite unsuitable. MGM grew tired of Flip, and Ub was asked to move on from the character.

Trivia Tidbit: Fiddlesticks – a Flip the Frog short by Ub – has gone down in history as the first full color animated feature. It was released on August 16, 1930.

Willie Whopper

In this second series from the Iwerks Studio, Willie is a young boy who tells many tall tales, which are illustrated on the film scream. Willie’s fantastic stories are in fact greatly exaggerated, or even outright make-believe, hence the term “whoppers.” His stories were usually prefaced by his memorable catchphrase, “Say, did I ever tell ya this one?” In the first short, Willie was tall and lanky. But over the course of the next several shorts Ub made him shorter and more roly-poly and “cartoon-like”, which made him more endearing to audiences. The series lasted only two years, from 1933-1934.

ComiColor Cartoon Fables

Produced from 1933-1936, ComiColor Cartoon Fables were independent stories based on popular fairy tales of the time, including Puss in Boots, The Three Bears, Sinbad the Sailor, and many others. The series was shot exclusively in Cinecolor – one of the early processes available for adding color to animated films. Several of the shorts in this series were filmed using a multiplane camera, which Ub built himself from the remains of a Chevrolet automobile.

Trivia Tidbit: Ub’s first version of the multiplane camera was later enhanced by Walt Disney’s artists to great acclaim, and it even landed Walt an induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2000.

A Well Run Dry

For all of Ub’s animation and technical expertise, the Iwerks Studio’s productions seemed to suffer a lack of charisma and imaginative storytelling. The studio lost its financial support in 1936, and closed shortly thereafter. In 1937 worked for Leon Schlesinger Productions to produce four Looney Tunes shorts starring Porky Pig and Gabby Goat. Ub directed two of the shorts. He also did a bit of contract work for Screen Gems directing several Color Rhapsody shorts. But Ub grew tired of fighting his way through opportunities that ultimately dried up, and looked back toward Disney to rekindle his earlier success.

Returning to Disney

Ub returned to work for Disney in 1940. This return was unusual to say the least. The Walt Disney Studios rarely rehired anyone who had left the company to work for a competitor. Ub’s rehiring was handled by director/producer Ben Sharpsteen, and Walt specifically stayed out of the details.

Once back with Disney, Ub took a position as creative technical director for the studio’s new optical print department. Ub stayed at the studio for the next three decades as a “technical troubleshooter” until his death in 1971. He is credited with “special processes” on several Disney films.

Ub is credited with developing the multi-head optical printer – an improved process for combining live-action and animation used in 1946’s Song of the South – for which he received an Academy Award. He also created the xerographic cel animation process 1961’s 101 Dalmatians.

Ub’s last credit for Disney films earned him another Academy Award. He assisted in the process of perfecting the travel matte system used in the “Feed the Birds” sequence of 1964’s Mary Poppins. In this memorable scene (which notably includes Walt Disney’s favorite song) hundreds of pigeons flock around St. Paul’s Cathedral, driving home the point of the heroic nature of charity toward those who really need it. The effect was so seamless that most people in the audience at the time never realized it was fully animated.

Beyond the Studio

Outside the studio, Ub worked quite a bit for Walt Disney Imagineering (called WED Enterprises at the time). He helped develop many of Disney’s theme park attractions during the 1960s, including Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion and Pirates of the Caribbean. In Walt Disney World, he made his mark on the Hall of Presidents. Ub’s talented mind touched the 1964 World’s Fair as well, where he assisted with “it’s a small world” and Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln.

Ub had one final major contribution outside Disney, when Walt allowed him to contract his services to Alfred Hitchcock to produce special effects for his 1963 film The Birds.

While Ub contributed a great deal to the Disney Studios from the 1940s onward, Walt held something of a grudge against his former partner. Walt worked with Ub on a professional level, but refused to rekindle their past friendship. Publicly, the two men respected each other and praised each other, but a chilly business relationship replaced what was once a warm friendship.

The Family Business

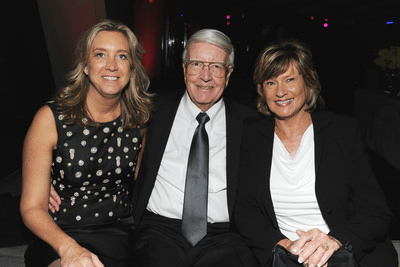

Ub had two sons – Don and David. In 1950, Don began a 35-year career working with the Walt Disney Company – some of that time working with his dad. Don’s notable contributions include the first 360 film techniques, 360-degree camera, and first Circle-Vision 360 film (America the Beautiful), and helping his dad in the development of the travel matte process for which his father was given an Academy Award.

Don’s daughter (Ub’s granddaughter) Leslie Iwerks also followed in the family business of entertainment – as a producer, director, and writer. Her notable contributions to Disney include 2007’s The Pixar Story and 2019’s The Imagineering Story. Leslie also wrote, directed, and produced 1999’s The Hand Behind the Mouse: The Ub Iwerks Story, which takes a deep dive into the life of her little-known grandfather.

The Legend Behind the Legend

Ub Iwerks died in 1971, five years after Walt Disney. Throughout his career, Ub provided much of the technical backbone for Walt’s creative ideas and initiatives. And though Walt received most of the public credit for progressing the place of animation in film, Ub was the technical wizard behind many of those accomplishments. In fact, Walt once referred to Ub as “the greatest animator in the world.” That’s the highest of praise for someone notoriously quiet on public praise.

Ub was deservingly named a Disney Legend in 1989 for his contributions to Disney animation and Imagineering. While Ub Iwerks may not be a household name to casual Disney fans, those familiar with the history of Walt and the Walt Disney company recognize the technical brilliance of this unassuming, yet remarkably talented artist.

Thanks for taking the time to learn a bit more about this lesser-known Disney Legend. Reach out with a message on social at: Instagram Facebook X

Thanks for learning about another Disney Legend! Follow along here for additional articles in this series. We’ll continue to highlight more of the extraordinary people who have shaped Disney’s storied history.

Sources:

Disney D23 Legend page – Ub Iwerks

Who Was Ub Iwerks? – Jim Korkis, July 1, 2020

Walt Disney’s Ultimate Inventor: The Genius of Ub Iwerks – Don Iwerks, Dec. 10, 2019

The Hand Behind the Mouse: The Ub Iwerks Story – Leslie Iwerks, 1999