(A version of this article was shared with Laughing Place and published on December 18, 2024.)

The Golden Age of the Disney Studios was a time of unparalleled talent, creativity, and progressive thinking. From the Silly Symphony series, to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, to Disneyland – mid-century Disney represented the peak of creative expression. Many artists and creative talents contributed to Disney’s Golden Age, and one of the most famous, influential, and talented may be the ever-zany animator Ward Kimball – one of Walt Disney’s famed “Nine Old Men.” This giant of Disney animation brought a sophistication to caricature animation, and also pushed the art of animation to new levels with his progressive ideas. And he did all this while operating his own railroad paradise and leading a Dixieland Revival jazz band.

Let’s peel back a few layers on Ward Kimball – one of Disney’s most interesting, talented, and renowned animators – in this edition of Disney Legends Spotlight.

Life in Locomotion

Ward Walrath Kimball was born March 4, 1914, in America’s upper Midwest region of Minneapolis, Minnesota. The son of a struggling traveling salesman, Ward and his family lived a somewhat nomadic lifestyle.

Because of his father’s constant traveling, Ward spent much of his early youth living with his grandmother. Not surprisingly, this is where many of his formative memories were made. A young Ward rode the local trolley cars with his grandmother for transportation. The constant presence of those dependable trolleys and trains made an impact on Ward that would last his whole life, beginning with his first recognizable drawing of a train locomotive completed when he was just three years old. Of course, Ward would grow to love more than trains. He excelled in cartoon drawing from a very young age as well, sketching out his first comic at the age of six.

By the time Ward was ten, his family moved to California, continuing that nomadic lifestyle that would see him attend over a dozen different schools throughout his youth. But the family travels finally leveled out when he was a teenager, and Ward was able to attend high school in Santa Clara with relative consistency.

The Budding Artist

Ward stood out in high school for his artistic abilities. As a freshman, he won first place in an art contest for cartooning, over everyone else in the school, including upperclassmen. In a high school music assembly, Ward was introduced to the trombone – an instrument that would add another critical passion to his multifaceted personality. The trombone was the instrument Ward felt he could have the most fun with, and he played it in the Santa Barbara High School band.

Ward didn’t travel far for college, attending the Santa Barbara School of the Arts to pursue a fine arts degree. He carefully balanced his animation course load with fine arts classes to round out his art portfolio, having been warned by others that cartooning work was often considered “beneath” the finer arts.

Beyond his college studies, Ward worked odd jobs to make money early in his career. The most unique job he held would prove to be a sign of his future career and social paths. Ward Kimball was a conductor for a music band playing at weekly Mickey Mouse Club gatherings at his local theater. The band would play music for the kids before the cartoons rolled, and Ward would stay and watch the shorts that followed. Through his regular exposure to Disney cartoons, Ward began to notice more sophistication in Disney shorts over other contemporary animation pieces. This experience, along with the urging of one of his art instructors, inspired Ward to take a shot at animating for the Disney Studios.

Making a Big Splash in the Disney Studios

In 1934 – at the age of 20 – Ward was hired by Disney as in-betweener, working on Mickey Mouse cartoons and other early Disney fare. Ward quickly excelled, progressing to assistant animator to study under Hamilton “Ham” Luske. Under Luske, Ward enjoyed opportunities to challenge his artistic abilities while working on the more progressive Silly Symphony projects – notably The Wise Little Hen (1934), The Goddess of Spring (1934), and The Tortoise and the Hare (1935).

By age 22, Ward was promoted again, to the position of full animator – the youngest in the company to hold that title. Continuing his work on the Silly Symphonies projects, Ward brought Toby Tortoise Returns (1936), Woodland Café (1937), and Mother Goose Goes Hollywood (1938) to life. Thanks to his solo work on Woodland Café, Ward’s grasshopper-turned-human would circle back his way in a few years, in the form of a certain 18-carat conscience.

Let’s look at some of Ward’s brightest moments in Disney animation and entertainment.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

Ward’s first crack at full feature animation came as part of the animation team for 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Ward was tasked with animating a lighthearted song sequence where the dwarfs feast on bowls of soup. The unfinished sequence was a work of beauty, but Walt Disney chose to cut it from the final film. Walt recognized that the presence of the scene was causing pacing issues with the film as a whole, slowing down the plot and failing to add character depth. While Walt’s decision was based on sound rationale and not at all a negative reflection on Ward’s animation work, Ward still felt crushed by the decision. He had invested months of time into the scene, and he felt discouraged to say the least. After a couple days of introspection, Ward visited Walt – preparing to offer him his resignation. Walt understood Ward’s feelings, and – knowing Ward’s immense talent and value to the studio – offered him a couple of alternate projects to animate. The first of these was the scene near the end of Snow White where the Evil Queen – in the form of the old witch – falls to her death. Those two opportunistic vultures who swoop down after the witch falls – those are all Ward Kimball.

Jiminy Cricket

Even bigger for Ward came his next feature character – Jiminy Cricket from the 1940 film Pinocchio. Ward’s work on the grasshopper in Woodland Café made him the perfect person to animate Jiminy. Ward’s initial sketches of the world’s most famous cricket were far too realistic for Walt’s desire. Walt told Ward to “make him cuter,” and the result is anthropomorphic perfection.

Casey Junior

While working his way up the Disney animation ladder, Ward was also deepening his lifelong love of trains. In fact, he would build model train layouts at home to blow off steam while working on Snow White. Ward’s love of trains was well-known throughout the studio, so it came as no surprise when Walt offered Ward the project of animating Casey Junior, the train in the 1941 film Dumbo. Walt’s instructions to Ward were explicit – “make it like your trains, but cartoon it up a bit.” Fun Fact: while working up initial drawings for the Casey Junior character, Ward gave the train a short, colorful conductor – a caricature of himself, hoping to memorialize himself in the film. Ultimately, the conductor was left on the cutting room floor, and Casey Junior managed his own affairs on the rails.

Also in Dumbo, Ward supervised the animation of the four crows who befriend Dumbo and Timothy Q. Mouse, giving them each lively personalities, following the model of the seven dwarfs in Snow White.

The Reluctant Dragon

Image: Disney

Ward’s personality around the Disney Studio was so amiable that he and fellow animators Fred Moore and Norm Ferguson were chosen to appear in a segment from the 1941 live-action/animated anthology film The Reluctant Dragon. Never one to be shy of the spotlight, Ward did most of the talking in the segment, while expertly animating Goofy for the first of his “How-To” shorts How to Ride a Horse.

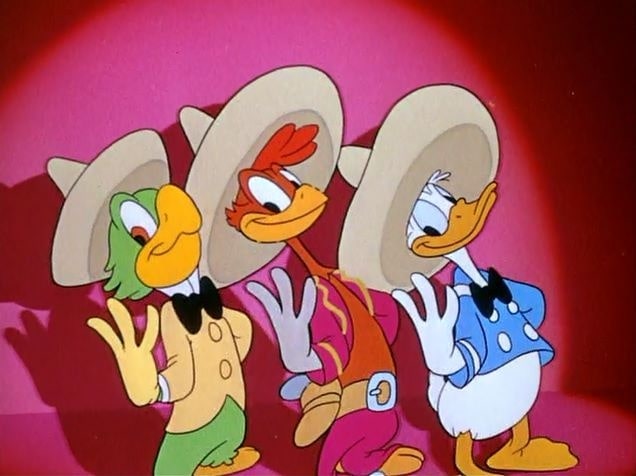

The Three Caballeros

Ward Kimball’s frenetic energy was infectious around the Disney Studio. His madcap pranks and jokes always brought laughs from the crowd gathered in his vicinity. Ward’s energy translated perfectly into the character trio known as the Three Caballeros, part of the 1944 live-action and animated package film of the same name. The Three Caballeros – consisting of Donald Duck, José Carioca, and Panchito Pistoles – were considered by Ward to be his favorite pieces of Disney animation. The sequence got high praise from Walt himself.

Cinderella

By 1950, the Disney Studios had developed a realistic style of animation. With every passing picture, Disney artists and animators were improving their ability to simulate life and natural movement in their characters. Ward still preferred the exaggerated and caricature-type features of the classic shorts. So when Ward was invited to work as directing animator on the 1950 film Cinderella, it wasn’t to animate any of the human characters. Ward was given Lucifer the cat, and Gus and Jaq – Cinderella’s friendly mice pets. The goofy hijinks of the mice, and the madcap battle between them and Lucifer fell in Ward’s sweet spot, and he excelled at the sequences involving these furry characters.

Alice in Wonderland

If ever there was a film full of characters meant for Ward Kimball, it was 1951’s Alice in Wonderland. Disney’s version of the classic Lewis Carroll tale leaned heavily on Ward’s comic cartooning sensibilities. As such, Ward acted as supervising animator for numerous characters, including Tweedledee and Tweedledum, the Walrus, Cheshire Cat, Mad Hatter, and March Hare.

Captain Hook

Image: Disney

People often compare Walt Disney to Peter Pan – the boy who never grew up. But Walt wasn’t the only eternally youthful soul in the Disney Studios. Ward Kimball shared that same zest for life. Ward’s over-the-top personality was a perfect fit for Captain Hook, as the two shared a propensity for larger-than-life expressions and exclamatory outbursts. In addition to being the directing animator for Captain Hook, Ward also directed the animation for John Darling and the Indian Chief.

Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom

Ward Kimball may have dressed for and celebrated the vintage Americana of yesteryear, but when it came to animation and art, Ward was always looking to push the envelope. In 1953, he got his chance with the educational short film Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom. The highly stylistic film leaned heavily on Ward’s distorted caricatures of people, while also introducing a variety of different (and edgy for the time) surroundings and backgrounds which were highly unusual for Disney animation. The project also allowed Ward to celebrate his love of music. Ward’s forward-thinking talent earned Disney the 1954 Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film, and the short was Disney’s first widescreen animated film produced in CinemaScope.

Man in Space

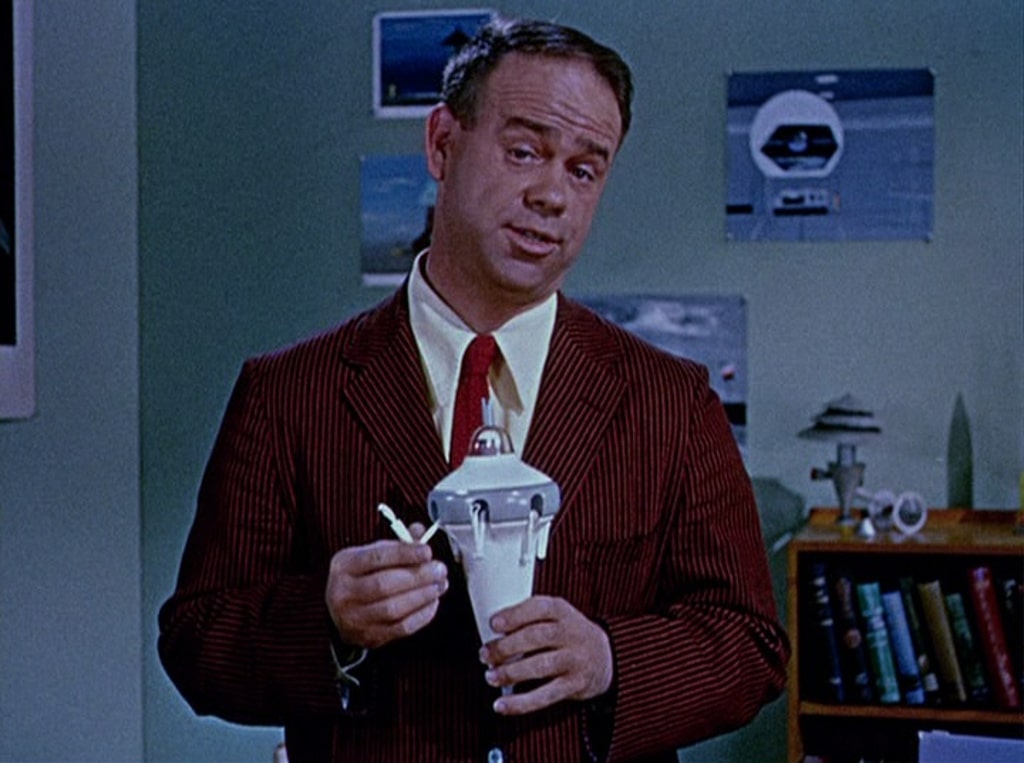

During the 1950s, television began to take hold in homes around America. Walt embraced the medium of television at a time when most film studios were spending their energy fighting against it. With the creation of Disneyland – Walt’s dream of a family theme park – now fully in development, Walt not only used television to entertain viewers – he used it to inform the public about “The Happiest Place on Earth” – planned to open in 1955. He did this through a weekly television show appropriately titled Walt Disney’s Disneyland.

Walt structured the Disneyland series in such a way as to spend individual weekly episodes exploring the concepts of four lands coming to the park – Adventureland, Fantasyland, Frontierland, and Tomorrowland. Walt had a stockpile of content for each category except Tomorrowland, so Walt brought in Ward to explore the concepts of space travel and futuristic transportation. Ward worked closely with several members of the studio, as well as noted German-American aerospace engineer Wernher von Braun. Von Braun had defected from Germany when he came to the grim realization that his efforts there were being used for the sole purpose of developing weapons of war. With support from von Braun, Ward wrote, directed, and produced a three-episode series of Tomorrowland content for the Disneyland show, including Man in Space (1955), Man and the Moon (1955), and Mars and Beyond (1957). Ward himself hosted the first two episodes.

Ward’s “Space” series did more to spark interest in spaceflight than any other media or educational material had to date. President Dwight Eisenhower used the material to catalyze U.S. interest and efforts in space exploration, which led directly to the development of the Saturn V Rocket of the Apollo Program. For this reason, Ward has always viewed the “Space” series as his greatest single achievement.

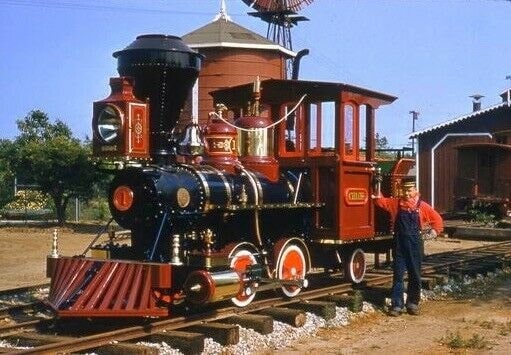

Ward’s Romance with the Rails

Ward Kimball’s infatuation with all things railroading began back when he was a small child, and his love of railroad culture never left him. While on honeymoon with his new wife Betty (who also had an interest in Americana and vintage motors and vehicles) – the newlyweds visited old towns of the American southwest, studying trains, cars, and other classic contraptions.

When Ward’s work at the Disney Studios turned stressful, he would blow off steam (pardon the pun) by immersing himself in his own railroading world. Ward’s collection grew over the years to include engines of multiple sizes, a full-size steam engine, a working roundhouse, water tower, windmill, and tracks that traversed his property in San Gabriel, CA. Ward called his backyard paradise the Grizzly Flats Railroad.

Ward’s railroading hobby was so well-known around the Disney Studio that it caught the attention of Walt, who had an affinity for trains of his own dating back to his childhood. Ward routinely attended meetings with the local railroad hobby club, which began to include Walt as well. In fact, Ward’s railroading passion is largely credited for resparking Walt’s love of locomotives, and his inclusion of trains as a foundational element in Disneyland.

In 1948, Walt was planning to attend the Chicago Railroad Fair. Knowing Walt was interested in going, and that he was unlikely to take his family with him on this particular trip, Ward decided to put a bug in Walt’s ear. He did this through Hazel George – Walt’s nurse – who had a close relationship with the boss. When Ward mentioned the Fair to Hazel, he was confident that word of his interest would get back to Walt. Ward’s plan played out to perfection, and Walt invited Ward to spend over a week with him attending the fair!

The pair did it up right on a cross-country trip aboard the Super Chief locomotive. They enjoyed the Fair (with some VIP treatment courtesy of Walt’s fame), the city of Chicago, and even a side trip to Deerfield Village in Detroit, to scout out some of Henry Ford’s collection of vintage Americana.

This historic trip served to germinate Walt’s dream of creating an entertainment park of his own. For Ward, he had the opportunity to enjoy some quality time with his boss outside of work. In one of their more introspective moments together, Walt admitted one thing to Ward – “I admire your courage to do what you want.” There was no doubt about it – Ward was his own man, and he lived his life unapologetically to its fullest.

The Music Man and His Dixieland Band

As if being a highly successful Disney animator and enjoying a time-consuming hobby like model railroading wasn’t enough, Ward Kimball continued to embrace the musical talent he found in himself back in high school. While working at the studio, Ward would take occasional breaks from animating to play his trusty trombone. Over time, others at the studio would occasionally play along with Ward, sharing a mutual love of jazz. What began as spur-of-the-moment jams started turning into more regular playing sessions, and led to the formation of an in-house Dixieland Revival jazz band Ward dubbed the Huggajeedy Eight.

The eight-member band did okay around the studio, but Ward felt the music deserved a little more dedication than some of his fellow studio musicians were prepared to offer. So Ward – along with fellow bandmates Frank Thomas and Harper Goff, went external from the studio and formed the San Gabriel Valley Blue Blowers with accomplished trumpet player Johnny Lucas.

The Dixieland Revival band improved to the point where they started playing professional gigs outside the studio. Looking to add a little extra color and flavor to the band, Ward took the advice of his wife Betty and added a gimmick to the band’s appearance – which came in the form of a turn-of-the-century antique fire truck. Ward got the band matching shirts, pants, suspenders, and hats, and they played a couple gigs as the Firehouse Five – arriving to gigs in a big bustle aboard their vintage fire truck. The alliterative name led to some confusion with the local nightclubs and patrons, as the band actually included seven members. A fix presented itself quite accidentally, when one of the band members added “Plus two!” to the band’s name when they were introduced at a gig. The momentary fix stuck, and the band officially became known as the Firehouse Five Plus Two.

The band continued to progress to a regional and then national level, becoming the leading Dixieland Revival band in the U.S. They made over a dozen LP records and toured clubs (including regular gigs at the famed Mocambo on Hollywood’s Sunset Strip), college campuses, and jazz festivals from the 1940s to the early 1970s. In their heyday of the late 1940s and early 1950s, they made appearances with Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters, appeared on variety shows, played in the Tournament of Roses Parade, recorded music for Disney productions, and played on the Mickey Mouse Club show.

For all their fame outside Disney, Walt was supportive of the musical moonlighting, as it gave his artists a creative outlet, while demonstrating support of a social culture around the studios.

Changing Times at the Disney Studios

As the 1950s wore on, Disneyland Park settled down to run as a well-oiled machine. While Walt loved spending time there, he was also able to return some of his attention to studio projects. With Walt’s added attention came the return of his demanding scrutiny. Ward Kimball found himself more on Walt’s radar, but not in a good way.

When Walt was preoccupied with Disneyland, Ward had enjoyed an increased measure of control over his projects. But with Walt’s return, the two clashed over project ideas. Walt assigned Ward to direct the 1961 live-action musical film Babes in Toyland. Ward’s involvement in the film was troubled from the start. He and Walt argued over casting, artistic design, and other directorial decisions. The last straw came when Ward was announced as director via a magazine article – when the decision to name him director had not yet been made official. Walt immediately replaced Ward as director with Jack Donoghue, and instead assigned Ward to write and direct select sequences within the film. This incident – which Ward viewed as a punishment – left a lasting mark.

Following Babes in Toyland, Walt assigned Ward to television animation tasks, which Ward felt were now beneath his abilities and aspirations. Ward became a primary animator for the character Professor Ludvig von Drake on a series of educational films, and assisted with other animation shorts as assigned by Walt. The relationship between the two had become strained to a point where it would never rekindle the magic of those earlier railroading days.

Ward did jump back into feature films, animating the Pearly Band – a group of musicians in the animated scene from 1964’s live-action/animation film Mary Poppins. This would prove to be Ward’s final major project while Walt was still alive.

Walt Disney’s death in December 1966 hit Ward hard. While the two had been estranged for a number of years, they still had a shared history full of laughs, mutual interests, and shared experiences. Ward had held out hope that one day the two might make amends. But with Walt gone, their strained relationship was memorialized as the final chapter of their history together.

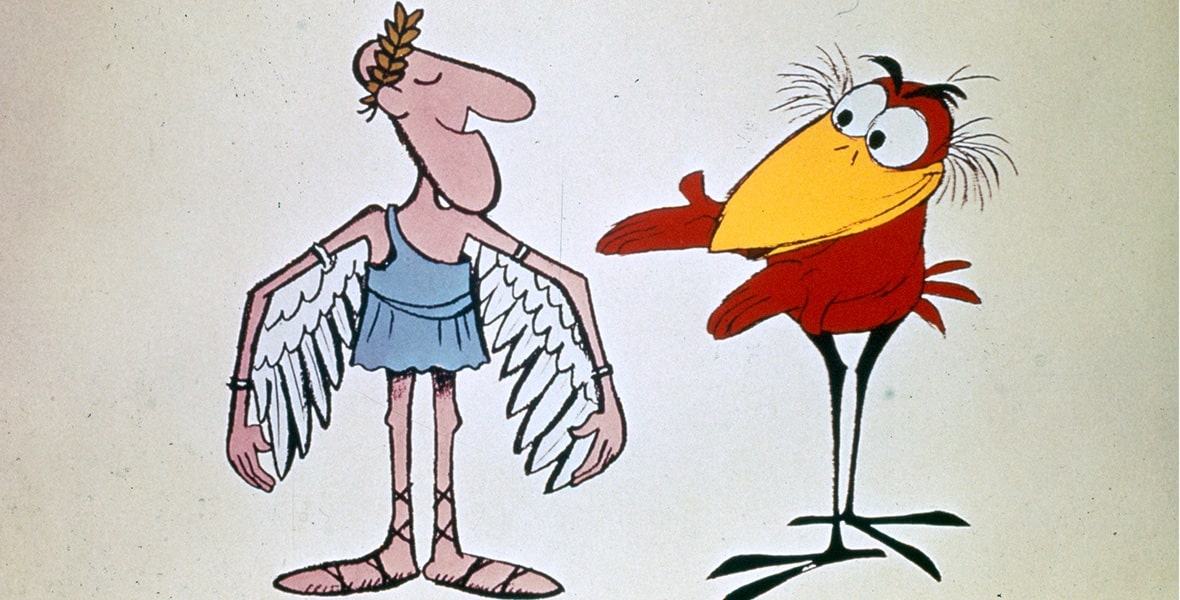

As the Disney Studio moved on without Walt, Ward continued to contribute meaningful content. In 1969, Disney released the animated educational short film It’s Tough to Be a Bird, with Ward as director. The short film won an Academy Award for Best Short Subject – Cartoons in 1970 and was nominated for a BAFTA Film Award for Best Animated Film in 1971. It’s Tough to Be a Bird is also recognized as the final animated cartoon short released by Disney in the golden age of American animation.

Ward’s Final Disney Studio Projects

Ward’s final studio projects included a role as animation director on another live-action/animation film – 1971’s Bedknobs and Broomsticks.

Ward got to flex his directorial muscles one final time as director/producer of The Mouse Factory, a 43-episode television series repackaging animated and live-action clips from Disney’s catalog. The series featured various guest hosts presenting various pieces of Disney material. Unfortunately for Ward, the series rated poorly among viewers, as well as many of his Disney contemporaries and executives, and was canceled after the second season.

Swan Song

Ward Kimball retired in 1973, but he continued to do some projects with Disney on a part-time basis. He and the other living members of Walt’s Nine Old Men were featured honorably in some publicity tours for the Disney corporation, which earned the members a new generation of fans and recognition.

Even in retirement, Ward had one last trick up his sleeve. His last hurrah with Disney came in a realm in which he had never worked – theme park attractions. Ward worked as designer for World of Motion, an attraction which opened with Disney’s EPCOT Center in 1982. The ride was designed by Ward and fellow Disney Legend Marc Davis. Ward and Marc both touched the attraction with their signature humor, in such moments as a used-chariot sale, and the world’s first traffic jam.

Fun Fact: A sea serpent which once appeared in a scene illustrating sea travel is officially known as the “Kimballum Horriblus” – named in honor of Ward Kimball. After World of Motion closed in 1996, the serpent was moved to the queue of the Hollywood Studios Backlot in Disney’s California Adventure, along with other items from the attraction. A toy-like depiction of Kimballum Horriblus lives in the Disneyland Paris version of “it’s a small world” where it mimics the scene from World of Motion by staring down a sailor doll in a rowboat.

Ward Kimball – A Genius in the Disney Studio

Ward Kimball enjoyed a much quieter life during retirement, spending more time with his wife Betty, and immersing himself even more in his beloved train collection. He passed away in 2002, at age 88, in Arcadia, California, of complications from pneumonia.

Walt Disney once called Ward Kimball the only genius at the Disney Studio. That is incredibly high praise from a man who rarely gives such direct compliments. But this compliment was a double-edged sword for Ward. On one hand, the high praise was supremely gratifying, but on the other, it created feelings of jealousy and resentment on the parts of other animators and creators within the studio. For better or worse, Ward carried this dichotomy of feelings from his fellow Disney creators for his whole career.

Ward was named a Disney Legend in 1989, along with his fellow Nine Old Men. Always one to stand out from the crowd, Ward added a sixth finger to his ceremonial handprints on his Disney Legends plaque.

Believe it or not, Ward Kimball is not featured on one of the famous Windows on Main Street. However, he does have a whole train in Disneyland. Steam locomotive #5 on the Disneyland Railroad went into service on June 25, 2005, and is appropriately named the Ward Kimball. The headlight of the locomotive features a gold leaf silhouette of one of Ward’s most famous creations – Jiminy Cricket.

With Ward himself possessing the facial features of a caricature, and a larger-than-life personality to match, it is fitting that he, along with fellow partner in crime Fred Moore, were memorialized as the vaudeville duo “Ward and Fred” in the 1941 Mickey Mouse short film The Nifty Nineties.

Ward Kimball has such a deep and storied history with Disney, and his talented fingerprints are all over the animation and humor from the Golden Age of the 1940s and 1950s. With a personality as deep as his talent, Walt will forever be recognized not only as one of the greatest animators of all time, but also as one of the most creative visionaries in the history of animation.

This was a long biography piece! If you stuck with me for the full article, thank you so much for reading, and I hope you enjoyed learning a bit more about Ward Kimball. This article was heavily inspired by the book The Life and Times of Ward Kimball: Maverick of Disney Animation by Todd James Pierce. Todd dives much deeper into Ward’s life in the book, and it’s a must-read for fans of Disney history and animation.

Check out more Disney Legends in our spotlight collection.

Offer a comment or share this article with a friend by reaching out on social at: Instagram Facebook X

Sources:

D23 – Disney Legend Ward Kimball

Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination – Neal Gabler, October 9, 2007

A Day with Ward Kimball in 1957, Jim Korkis, August 21, 2013