(A version of this post was shared with Laughing Place on January 29, 2023.)

So you know about the park bench, the orange groves, and the high heel shoes in pavement. Disneyland is a literal treasure trove of magical moments, from the moment of conception through the present day. It’s a place dreamed up by Walt Disney, and made possible by the tireless contributions of countless others. Let’s take a look at one of the most legendary moments in the creation of Disneyland, and the man responsible for its success, in this edition of Disney Legends: The People Who Made Disney History.

The Dream

Most Disney fans know the story of how Walt’s dream of Disneyland began to take shape. Legend has it Walt came up with the idea while sitting on a bench at Griffith Park, while his daughters Diane and Sharon rode the merry-go-round. Walt wanted to build a place where children and parents could have fun together (and where he could play as well!).

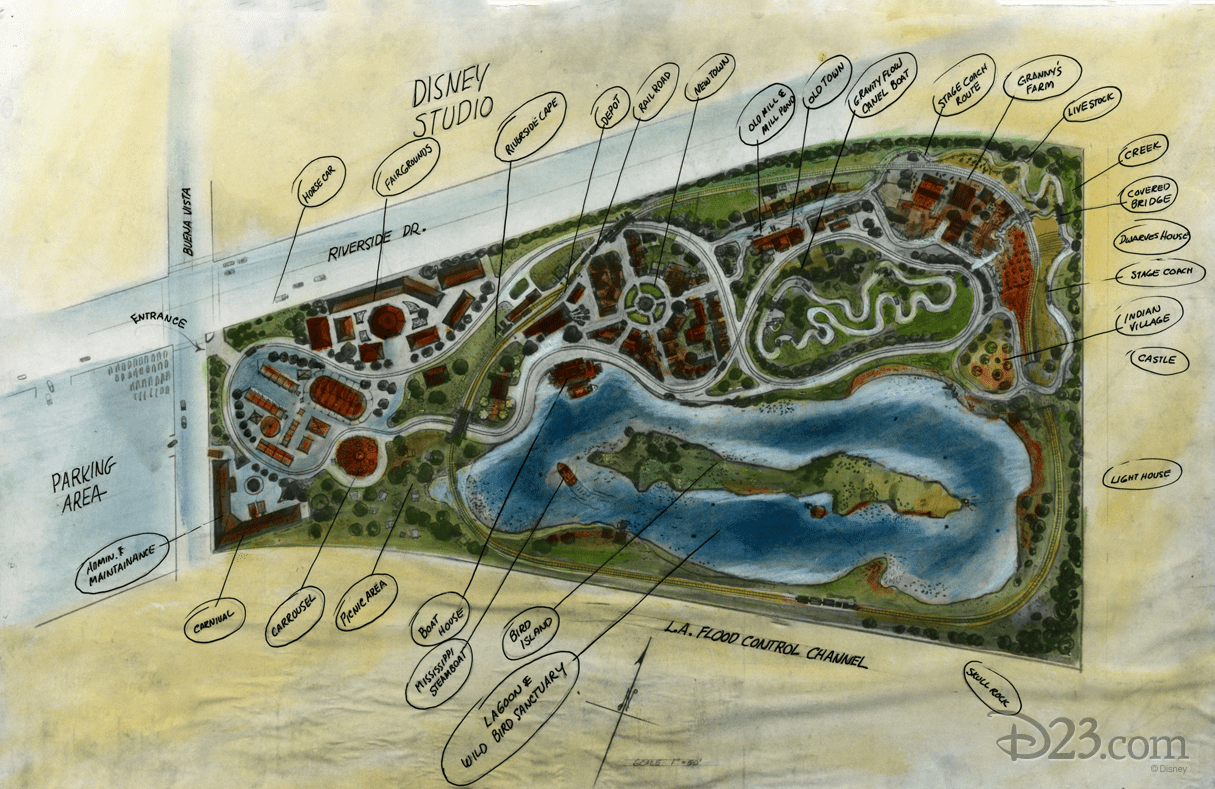

Walt’s park started out small, with only a few acres to be located across the street from the Disney Studios. The initial incarnation of Walt’s dream was called Mickey Mouse Park, with the rendering below drawn by Disney artist Harper Goff.

But Walt’s vision grew larger, and before long the small space near the studio lot was not big enough to hold all his ambitious ideas. Walt needed more land, and more money, to make his Disneyland a reality.

Most of his contemporaries at the time thought his idea for a new themed park was silly, and consensus among them was that the park would close within six months of opening, proving Walt’s idea to be a failure. The doubting sentiments of Walt’s contemporaries gave him even greater confidence that he was onto something big, and now he just needed to prove it.

Money, Money, Money

In December 1952, Walt took the first major step, founding WED Enterprises – an arm of the company tasked with designing Disneyland (WED would also be financially responsible for the park – separate from the Studios – in the event the park did indeed fail). Walt injected WED with some initial budget which he peeled from his own bank account and personal property, but WED was quickly burning through the money. Walt didn’t have enough in WED to build Disneyland, and he needed some financial support, in the form of a major bank loan.

On Saturday, September 26, 1953 – with his brother Roy heading from Burbank to New York in just a few couple days – Walt needed something to show the bankers, to convince them to invest in his park. It was at this moment, on an otherwise quiet and lazy Saturday morning, that Walt entered the legendary “Lost Weekend.”

But who would put Walt’s vision on paper? He knew exactly who he wanted. Someone who used to work for Disney, but now worked for a competitor – 20th Century Fox. Someone named Herb Ryman.

Enter Herb Ryman

Herbert Dickens Ryman Jr. – born in June 1910 – was an artist extraordinaire, specializing in watercolor, oils, and pen & ink sketches. He wanted to study art in college, but his mother preferred a more practical career path for him in the medical field. When Ryman got deathly ill and appeared to be dying from Scarlet Fever, his mother softened and allowed him to pursue his dream with his remaining time. Not only did Ryman survive, but he thrived at the Art Institute of Chicago, graduating cum laude.

Ryman worked for Walt in the Disney Studios for several years in the late 1930s and early 1940s, serving as art director for films such as Dumbo and Fantasia. He was also invited to join “El Grupo” – Walt’s 1941 goodwill tour of South America, which included a “who’s who” of Disney artists of the day. The experience of El Grupo inspired several subsequent “package films”, including The Three Caballeros and Saludos Amigos – both of which Ryman also contributed to.

Ryman left the Disney Studios in the mid-1940s to work on a series of films for 20th Century Fox. Always looking for inspiration, Ryman took leaves of absence in the summers of 1949 and 1951 to tour with the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. During these summers, Ryman lived among the performers and documented circus life through his paintings.

The Lost Weekend

On that fateful Saturday morning in September 1953, Ryman was peacefully painting at his home when Dick Irvine – an art director Walt had recently hired to take the lead on his Disneyland project – called him. Irvine mentioned to Ryman that Walt wanted to speak with him. Walt took it from there.

According to biographer Neal Gabler, author of Walt Disney: The Triumph of American Imagination:

Walt got on the phone and asked him how long it would take for him to get to the studio. Ryman said fifteen minutes if he came as he was, a half-hour if he dressed. Walt told him to come as he was and Walt would meet him at the studio gate.

A half-hour later, Ryman arrived at the studio. Walt greeted him and quickly told him “Herbie, we’re going to build an amusement park.” After a bit of back-and-forth about his plans, Walt cut to the chase. Biographer Bob Thomas recounted some of the conversation in Walt Disney: An American Original:

“Look, Herbie, my brother Roy is going to New York Monday to line up financing for the park. I’ve got to give him plans of what we’re going to do. Those businessmen don’t listen to talk, you know; you’ve got to show them what you’re going to do.”

“Well, where is the drawing? I’d like to see it.”

“You’re going to make it.”

To this, Ryman’s first response was “No, I’m not.” With a complete unfamiliarity about the project, Ryman felt he’d embarrass both himself and Walt by taking on the task.

But Walt was a persuasive man, and Disneyland was extremely important to him. Historian Michael Broggie recounts the next portion of the event in Walt Disney’s Railroad Story:

“Herbie, this is my dream. I’ve wanted this for years and I need your help,” [Walt] pleaded. “You’re the only one who can do it. I’ll stay here with you and we’ll do it together.”

The Drawing

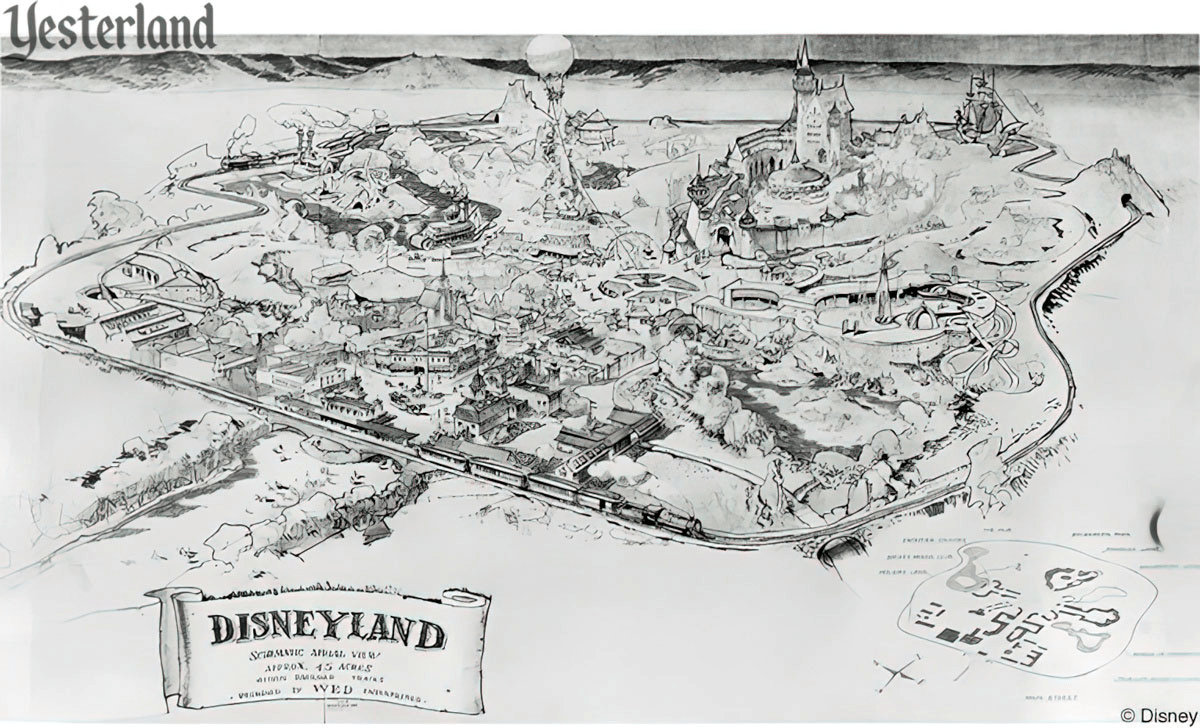

As was usually the case, Walt’s plea won out, and Ryman begrudgingly agreed to help. Fast-forward over forty hours later. The pair had spent the entire weekend in the studios, carefully crafting what would become the most legendary piece of art in Disney Parks history. Ryman balanced drawings provided by Dick Irvine with Walt’s first-hand descriptions of his Disneyland dreams.

When Irvine walked into the studios on Monday morning, Walt and Ryman looked quite worse for the wear. But they had completed their mission. Walt’s illustration of Disneyland was ready for primetime. Roy headed off to New York, where he would secure some of the critical financing needed to continue Walt’s dream. Less than two years later, Disneyland would become a reality.

A Happily Ever After Ending

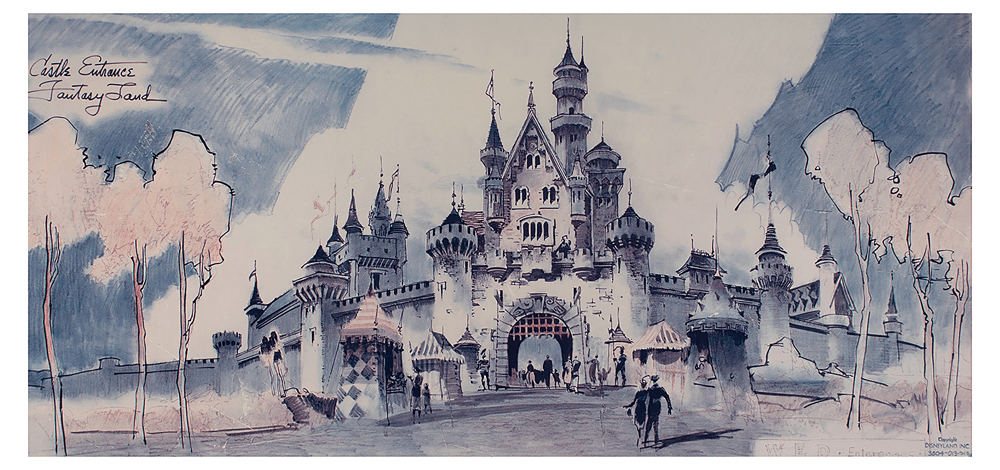

As for Herb Ryman? He was quickly officially hired by Walt, and he continued to design portions of Disneyland, including Sleeping Beauty Castle and New Orleans Square. He also drafted Magic Kingdom’s Cinderella Castle. Even after he retired from Disney in 1971, he continued to consult for the company, contributing conceptual drawings for EPCOT Center, Tokyo Disneyland, and Disneyland Paris.

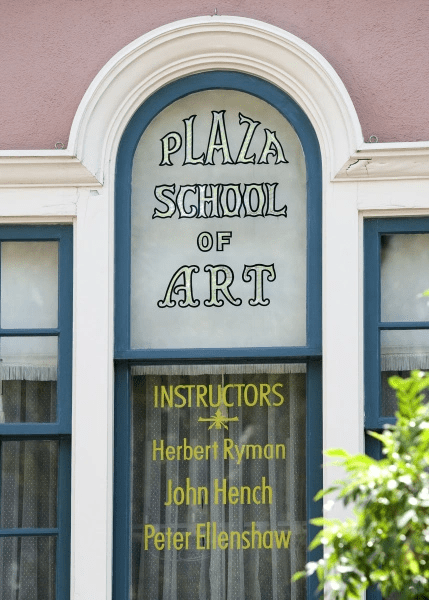

Herb Ryman was named a Disney Legend in 1990. He is honored, along with two others, with his name on a Main Street window, above Main Street Photo Supply Company, stating:

Plaza School of Art

Instructors

Herbert Ryman

John Hench

Peter Ellenshaw

There are a handful of these pivotal moments in Disney history, and thanks to Herb Ryman, Walt’s “Lost Weekend” proved to be the first, biggest moment in Disney Parks history. In hindsight, I’d hardly call that a Lost Weekend.

If you enjoyed this post, please feel free to share using one of the buttons below (or you can copy/paste the URL).

Find Facts and Figment on social! Instagram Facebook X

Follow along here for additional articles in this series. We’ll continue to highlight more of the extraordinary people who have shaped Disney’s storied history.

Sources:

Walt Disney: The Triumph of American Imagination – Neal Gabler, 2006

Walt Disney: An American Original – Bob Thomas, 1976

Walt Disney’s Railroad Story – Michael Broggie, 1997